My impression about Percolator was that it could enable transactional capabilities on a regular distributed KV store, but the overhead of the 2PC + Raft process was significant. A few days ago, I heard that CockroachDB (CRDB) has made some engineering optimizations compared to Percolator. I decided to learn about these implementation ideas.

Similar to Percolator, CRDB also implements decentralized transaction management for multi-row transactions. The challenge lies in the potential concurrency conflicts for each row operation. The transaction commit protocol uses the atomic transaction capability of a local transaction to arbitrate concurrent operations and to advance exception recovery for different stages.

Unlike Percolator, CRDB does not rely on an existing general-purpose KV store. Instead, it can design more end-to-end, using its own storage format for transaction metadata.

This article is organized as follows:

- Transaction metadata and regular transaction process

- Concurrency control

- Parallel Commit optimization

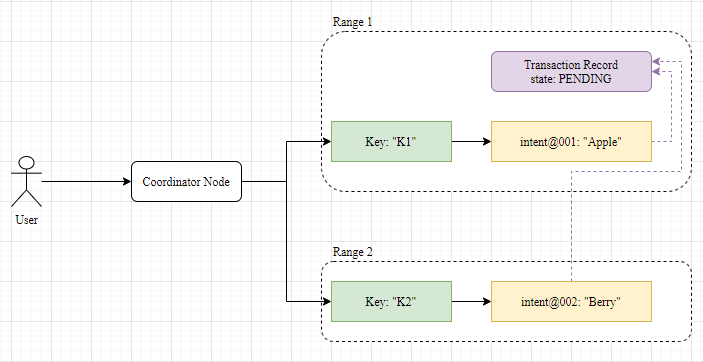

TransactionRecord and WriteIntent

CRDB shards data into ranges, similar to regions in TiDB. Each range is about 64MB in size, and local transactions can be executed within each range.

CRDB allocates separate areas within each range to store TransactionRecord and WriteIntent, which are the main metadata related to transactions:

- TransactionRecord stores the transaction status (PENDING, COMMITTED, ABORTED) and has a timeout.

- WriteIntent acts as a write lock and temporary storage for new data. At most one WriteIntent can exist for the same key at the same time, used for pessimistic mutual exclusion. Each WriteIntent in a transaction points to the same TransactionRecord.

Recall that in Percolator, the first written row in a transaction is chosen as the Primary Row, and other rows point to the Primary Row. Concurrent operations on other keys align with the Primary Row, and the commit status stored in the Primary Row is used to determine the overall transaction status.

In CRDB, the first row in a transaction also plays a special role, with the TransactionRecord stored in the same range as the first row. All WriteIntents in the transaction point to this TransactionRecord. This is a notable difference from Percolator at first glance:

The Coordinator Node is the node that users connect to when accessing the CRDB cluster. It takes on the role of the Coordinator, driving the transaction process.

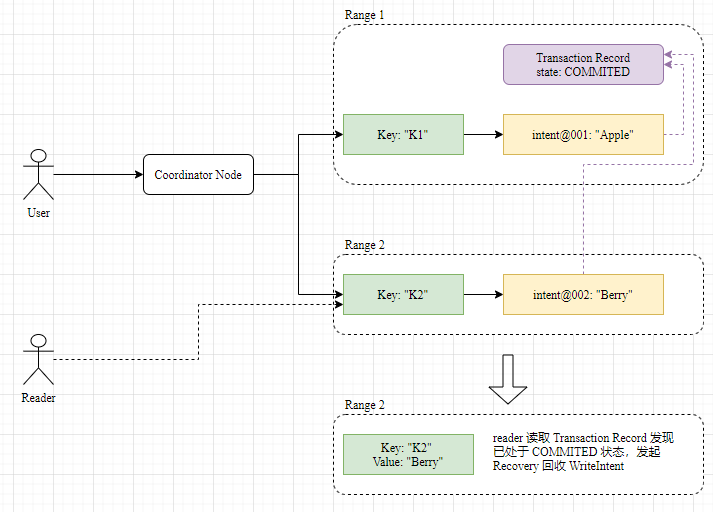

After all keys have completed the first phase of writing, the Coordinator drives the transaction into the commit phase of the two-phase commit: marking the TransactionRecord as COMMITTED, which serves as the Commit Point. It can then return a successful commit to the user. The Coordinator then drives the asynchronous cleanup of WriteIntents. If a user accesses a WriteIntent during this period, they will query the status of the TransactionRecord and perform cleanup operations:

Eventually, both WriteIntent and TransactionRecord are cleaned up, completing the transaction.

Unlike Percolator, CRDB, as a Serializable isolation level, has only one commit timestamp for the entire transaction, rather than two timestamps (startTs and commitTs). This timestamp is only used for MVCC, and pessimistic concurrency control through locking is used for concurrency control. This single timestamp also reflects the logical aspect of Serializable: Serializable is equivalent to executing all transactions sequentially, with the start and end of a transaction occurring in an atomic time.

What if the Coordinator Fails?

Each range already has Raft, and the upper layer can generally consider them reliable. However, the Coordinator is a single point, and the probability of it failing midway is not low. It cannot rely on the Coordinator to ensure transaction reliability. In design, CRDB arranges the Coordinator to drive the complete lifecycle of the transaction. However, if the Coordinator fails, other visitors encountering leftover WriteIntents can still drive the cleanup process to complete the transaction normally. This is the same idea as in Percolator:

- If the transaction is interrupted before the Commit Point, the visitor of the relevant key drives the Rollback process, marking the transaction status as interrupted and cleaning up the transaction metadata on the key.

- If the transaction is interrupted after the Commit Point, the visitor drives the Roll Forward process, making the latest written value effective and cleaning up the transaction metadata.

Unlike Percolator, where each lock has a timeout, the timeout in CRDB is maintained in the TransactionRecord, and WriteIntent does not have a timeout. The Coordinator periodically sends heartbeats to the TransactionRecord to keep it alive. If other visitors find that the TransactionRecord has timed out, they will assume that the Coordinator has died and initiate a cleanup process, marking the TransactionRecord as ABORTED.

When accessing a Key and finding a Write Intent, you follow the reference of the Write Intent to find the TransactionRecord and handle it differently based on its status:

- If it is in the COMMITTED state, you directly read the value in the WriteIntent and initiate the cleanup of the WriteIntent.

- If it is in the ABORTED state, the value in the WriteIntent is ignored, and the WriteIntent is cleaned up.

- If it is in the PENDING state, it means you have encountered an ongoing transaction:

- If the transaction has expired, it is marked as ABORTED.

- If the transaction has not expired, conflict detection is performed based on the timestamp.

The logic for conflict detection will be detailed later.

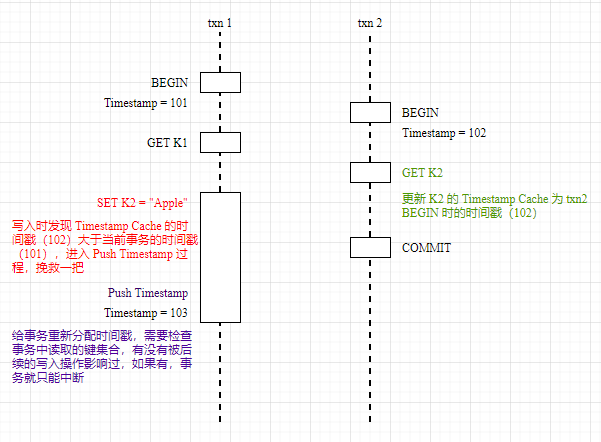

Timestamp Cache and Read Refreshing

Write Intent can be used to track write conflicts, but since CRDB is Serializable isolation level, it also needs to track read records and perform conflict detection for both read and write operations.

CRDB’s approach is to save a Timestamp Cache for each range, which stores the timestamp of the most recent read operation for the keys in that range. As the name suggests, the Timestamp Cache is stored in memory within the range and is not replicated through Raft.

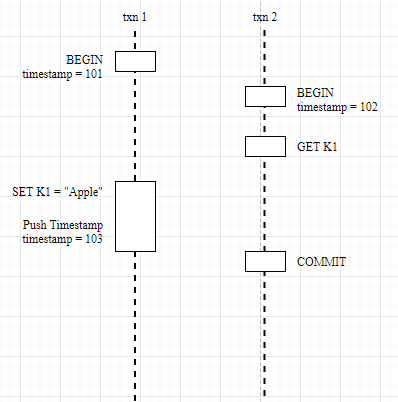

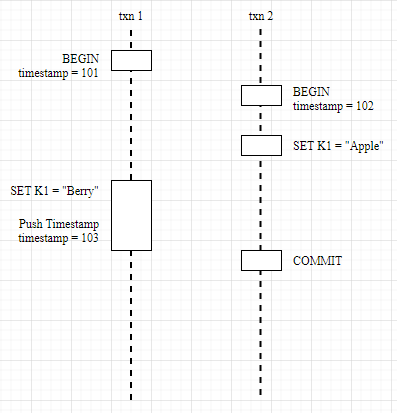

Whenever a write occurs, it checks whether the timestamp of the current transaction is less than the latest value in the Timestamp Cache for that Key. If it is, it means that the current transaction’s write operation will invalidate the content read by the most recent other transaction. In a conventional Serializable transaction process, this should declare the transaction conflict as a failure:

However, CRDB does not directly exit the transaction in conflict here but tries to salvage it. The idea is: If the current transaction conflicts with another transaction in a Write after Read scenario, can I push the transaction’s timestamp to the current time and then run the Write After Read conflict check again?

However, executing Push Timestamp also requires certain prerequisites, namely whether there are new write operations for the keys read by the current transaction within the range of [original timestamp, new timestamp]. If there are unfortunate new writes, it cannot be salvaged, and the transaction conflict must be considered a failure. This check is called Read Refreshing.

Push Timestamp is lighter than directly reporting a transaction conflict and then retrying the entire transaction at the user level. It is also more user-friendly. In our business code, we rarely retry transactions. Saving a salvageable transaction means one less exception on Sentry. I think this is one of the better aspects of pessimistic concurrency control compared to optimistic concurrency control.

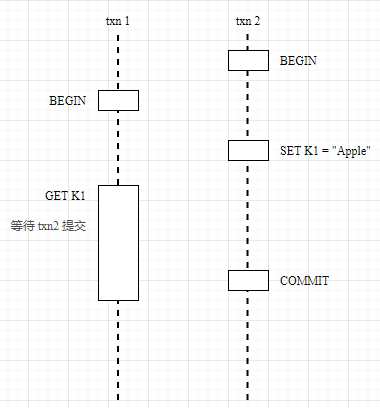

Transaction Conflict

There are several scenarios for transaction conflict:

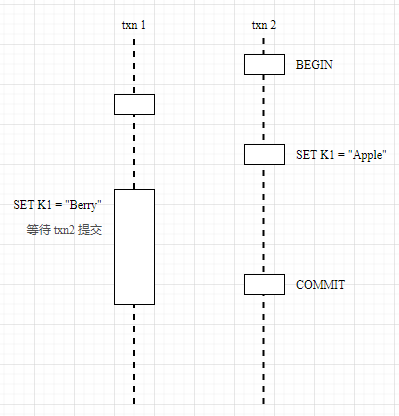

Read after Write: Reading a Write Intent from an uncommitted transaction with a timestamp less than the current transaction. In this case, the current transaction needs to wait for this transaction to complete before reading the key value. CRDB will add the current transaction to the TxnWaitQueue to wait for the dependent transaction to complete. If the timestamp of the Write Intent read is greater than the current transaction, there is no need to wait, and the key value can be read directly according to MVCC, equivalent to reading a snapshot at the current transaction time.

Write after Read: When performing a write operation, the timestamp of the current transaction must be greater than or equal to the most recent read timestamp of the Key. If there is a conflict, try to continue the transaction execution by pushing the timestamp.

Write after Write: When performing a write operation, if an earlier uncompleted Write Intent is encountered, it needs to wait for that transaction to complete first. If a newer timestamp is encountered, push the timestamp of the current transaction back.

In summary, there are two strategies when a transaction encounters a conflict:

- Waiting: Primarily used when the start time of other transactions is earlier than the current transaction, encountering dependencies, and the current transaction waits for other transactions to complete before executing;

- Push Timestamp: Primarily used when the start time of the current transaction is earlier than other transactions, encountering dependencies, and attempts to push the current transaction’s timestamp back to make it later than other transactions. However, pushing the timestamp requires a pre-check through Read Refreshing to ensure that the current transaction’s read set has not been modified; otherwise, the transaction must also be interrupted;

Parallel Commit

The original performance of Percolator would be quite impressive: for each row of data, a Prewrite requires a replication process, and then each row of data Commit requires another replication process. If Raft is used for replication at the lower level, N rows of data would mean running 2 * N Raft consensus processes, each of which would at least fsync() once. In contrast, a single-machine DB, regardless of the number of rows in the transaction, only requires one fsync().

To optimize the performance of the commit, CRDB first implemented Write Pipelining. Multiple rows of data written in a transaction are queued into a pipeline and the consensus process is initiated in parallel. This reduces the waiting time from O(N) to O(2), with Prewrite and Commit each going through two rounds of consensus processes.

Is it possible to further optimize the commit process? CRDB introduced a new commit protocol called Parallel Commit, which can complete the commit in one round of consensus. The general idea is: in a two-phase commit, as long as all prewrites are completed, the commit cannot fail and can safely return a successful commit to the user.

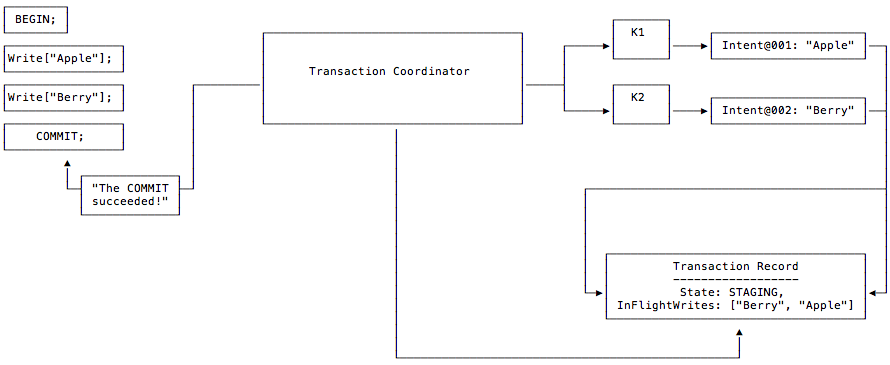

So, how to determine that all writes are in a completed state? Here, two modifications are made to the Transaction Record: 1. Introducing the STAGING state to indicate that the transaction has entered the commit phase; 2. Adding the InFlightWrites field to record the list of keys currently written by the transaction. Additionally, the Transaction Record is no longer created when the transaction starts, but when the user calls Commit(), at which point the keys modified by the transaction are known.

According to the official documentation, the general steps of a transaction are:

- The client contacts the Transaction Coordinator to create the transaction;

- The client attempts to write a Write Intent with the key K1 and value “Apple”, which generates the ID of the Transaction Record and points the Write Intent to it, but does not actually create the Transaction Record;

- The client attempts to write a Write Intent with the key K2 and value “Berry”, similarly pointing it to the ID of the Transaction Record, which also does not yet exist;

- The client initiates Commit(), at which point the Transaction Record is created, setting its state to STAGING and its InFlightWrites to point to the two Write Intents [“Berry”, “Apple”].

- Waiting for the concurrent writes of the Write Intent and Transaction Record to complete, the user can be returned as successful;

- The Coordinator initiates the commit phase, setting the Transaction Record to the COMMITTED state and flushing the Write Intent into the main storage;

If the Coordinator crashes after the commit, when an accessor reads the key of the Write Intent, it will first read the corresponding Transaction Record and then determine whether each key has been successfully written through InFlightWrites:

- If not successful and the Transaction Record has timed out, the accessor will drive the Transaction Record to enter the ABORTED state;

- If all keys have been successfully written, it is considered to be in the Implicit Committed state, and the accessor will drive the Transaction Record to enter the explicit COMMITTED state and flush the related Write Intent into the main storage;

It can be seen that although Parallel significantly reduces the waiting time of the commit process, the exception recovery process driven by the accessor becomes more expensive. In the normal process, CRDB still hopes that the commit process driven by the Coordinator will be completed as soon as possible, making the recovery process driven by the accessor only a last resort.

References

- CockroachDB: The Resilient Geo-Distributed SQL Database

- https://www.cockroachlabs.com/docs/dev/architecture/transaction-layer.html

- https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/85001198