Badger is an open-source LSM Tree KV engine developed by dgraph. Compared to leveldb, it introduced various improvements such as KV separation, transactions, and concurrent compactions, making it a more production-ready storage engine in the Go ecosystem. Let’s take a look at its transaction implementation.

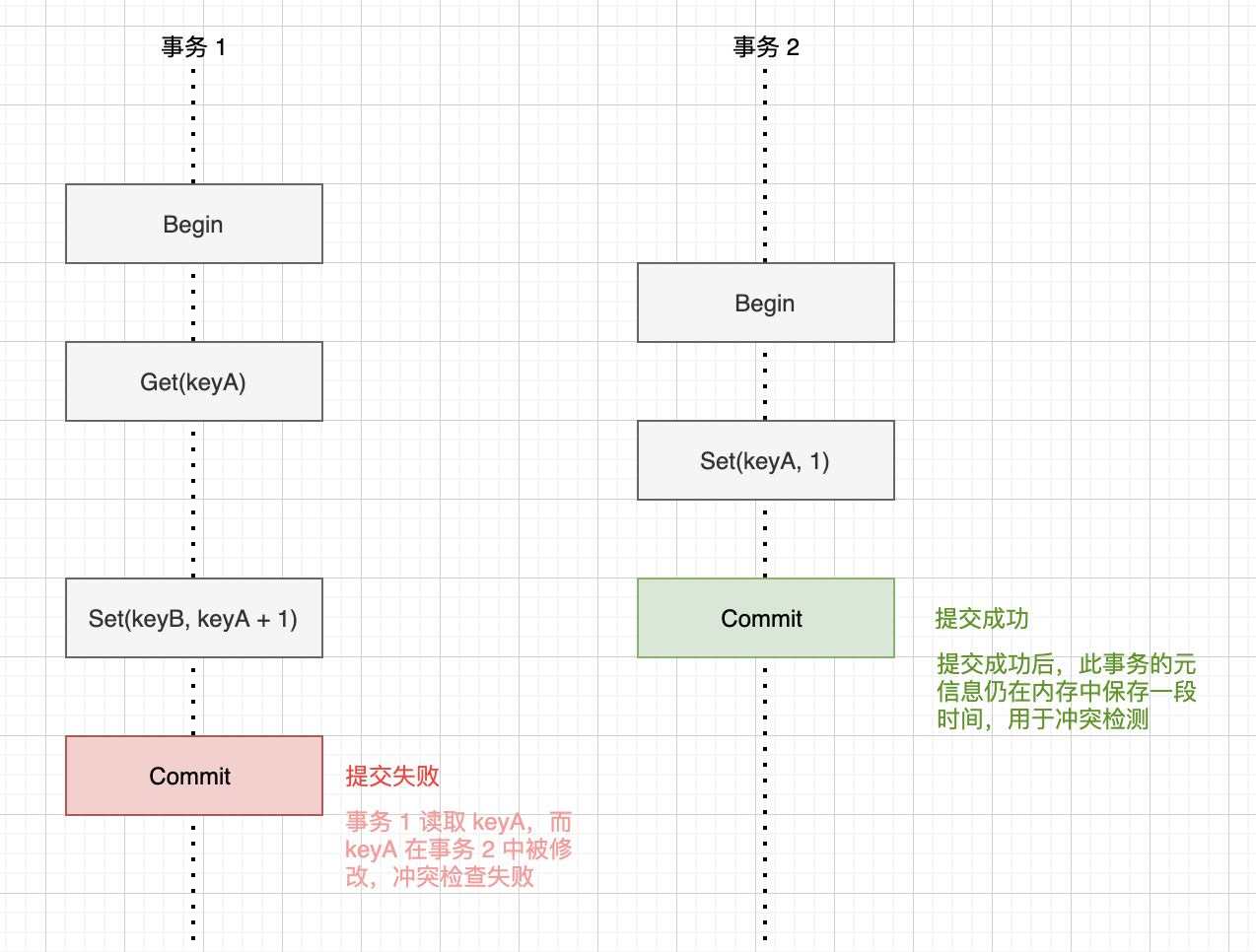

Badger implements optimistic concurrency control (OCC) transactions with Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) level. Compared to Snapshot Isolation (SI), SSI not only tracks write operations for conflict detection but also tracks read operations within transactions. It performs conflict checks during commit. If any data read by the current transaction has been modified by other transactions during the transaction’s execution period, the commit will fail:

Transaction Lifecycle

The lifecycle of an optimistic concurrency control transaction can be roughly divided into four stages: timestamp assignment, read-write tracking, commit, and cleanup:

- Transaction Start: Obtain a timestamp at the start of the transaction.

- Transaction Execution: Track the keys involved in the transaction’s read and write operations. During the transaction, read operations are based on the snapshot at the start time, and write contents are temporarily stored in memory.

- Transaction Commit: Perform conflict detection based on the keys tracked in the transaction, obtain the timestamp at the commit time, and commit the writes.

- Cleanup of old transactions: When active transactions complete, transaction-related data that is no longer needed (such as snapshot data and conflict detection data) and can be released.

To manage the transaction lifecycle, there’re two parts of metadata need to be managed:

- At the individual transaction level, we need to record the list of keys read and written, as well as the transaction’s start timestamp and commit timestamp. This information is maintained in the

Txnstruct - At the global level, we need to manage the global timestamp, the list of recently committed transactions (used for conflict checking in new transaction commits against the range of transactions committed between the start and commit timestamps), and the minimum timestamp of currently active transactions (used for cleaning up old transaction information). This information is maintained in the

oraclestruct

The timestamp obtained here is not physical time, but logical: all data changes come from the moment of transaction commit, so the timestamp only increments when a transaction commits.

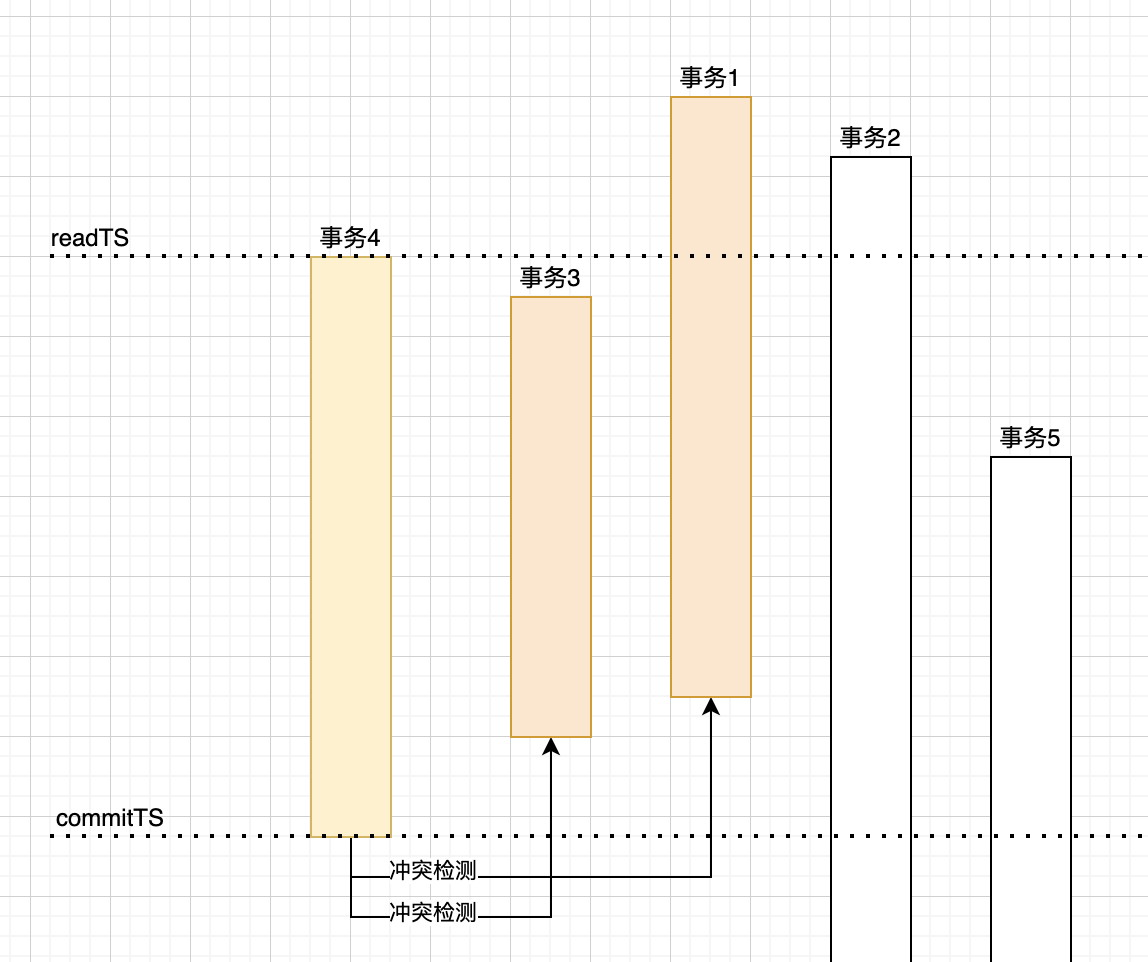

Using the above diagram as an example, when transaction 4 commits, it needs to perform conflict detection with transactions 3 and 1, because the commit times of transactions 3 and 1 are between the start and commit of transaction 4. If there is an overlap between the keys written by transactions 3 and 1 and the list of keys read and written by transaction 4, a conflict is considered to exist.

Next, let’s go through the related processes in badger along these four stages of the lifecycle.

Transaction Start

The entry point for starting a new transaction is in the db.newTransaction() function. This function is relatively simple. Apart from initializing a few fields, the only part with behavioral semantics is the line txn.readTs = db.orc.readTs() where timestamp assignment is requested.

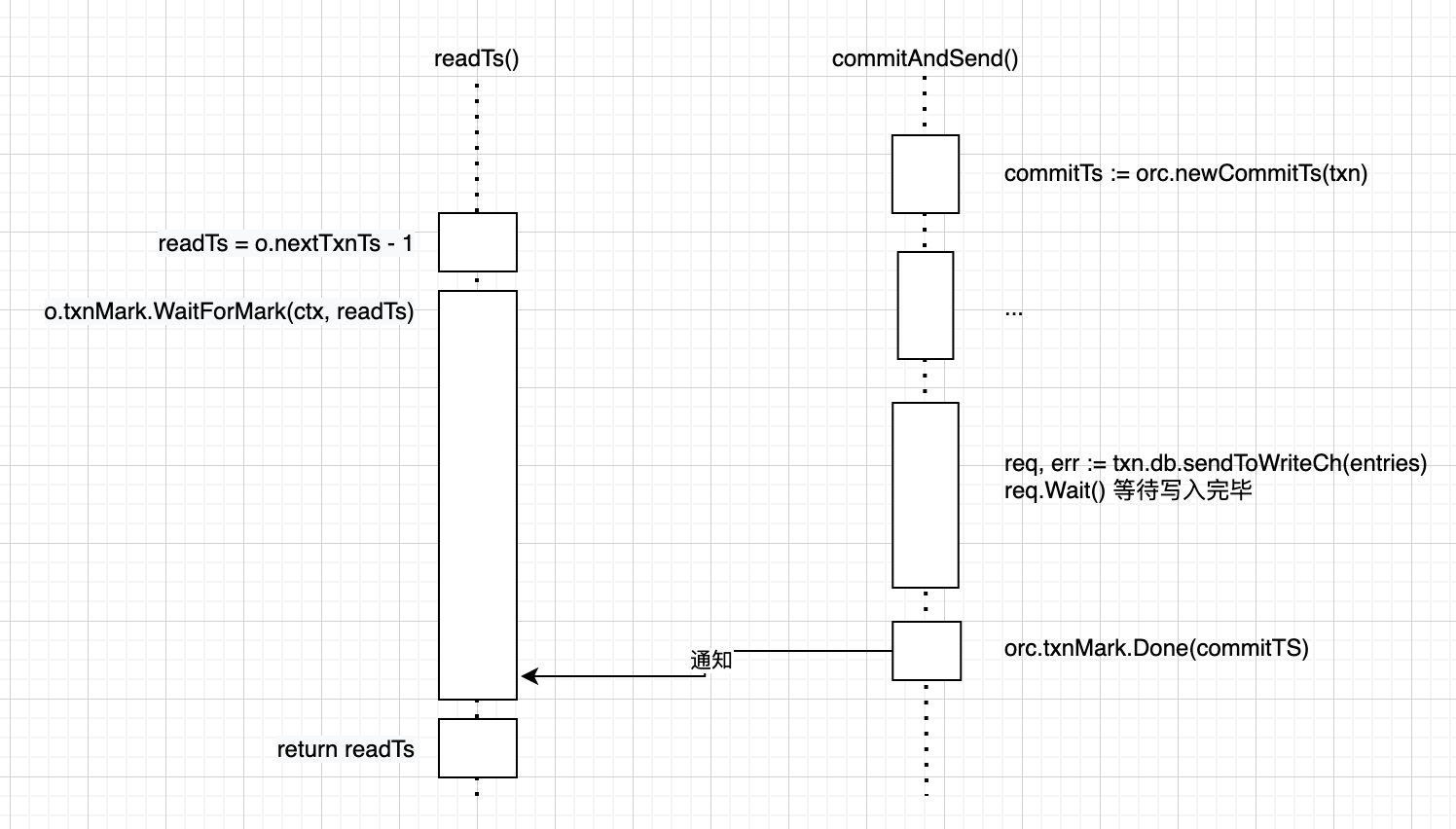

Let’s look at the implementation of the readTs() function:

func (o *oracle) readTs() uint64 {

// Ignore isManaged part of the logic

var readTs uint64

o.Lock()

readTs = o.nextTxnTs - 1

o.readMark.Begin(readTs)

o.Unlock()

// Wait for all txns which have no conflicts, have been assigned a commit

// timestamp and are going through the write to value log and LSM tree

// process. Not waiting here could mean that some txns which have been

// committed would not be read.

y.Check(o.txnMark.WaitForMark(context.Background(), readTs))

return readTs

}

The timestamp assignment logic is simple, directly copying from the nextTxnTs field recorded in the oracle object.

There’s a detail here: as mentioned earlier, timestamp increments occur at transaction commit, and there will be a time window where the timestamp has incremented but the write has not yet been persisted to disk. If a transaction starts at this time, it would read old data instead of the snapshot after the timestamp. The solution is to wait for the transaction of the current timestamp to complete writing before starting the transaction.

The txnMark field is a WaterMark struct, which internally maintains a heap data structure that can be used to track changes in transaction timestamp segments.

In addition to waiting for transactions related to the current timestamp to complete writing based on txnMark, there’s also a line o.readMark.Begin(readTs) in the readTs function. readMark is aslo a WaterMark struct like txnMark, but it doesn’t use the WaterMark struct’s ability to wait for positions. It only uses its heap data structure to track the timestamp range of currently active transactions, used to find out which transactions can expire and be recycled.

Transaction Execution

During transaction execution, writes are temporarily stored in the pendingWrites buffer in memory. In managed mode, if multiple writes are made to the same key within a transaction, the historical version data inserted within this transaction is stored in the duplicateWrites buffer. We’ll ignore the duplicateWrites field for now.

Read operations during a transaction will first read from the pendingWrites buffer, and then read data from the LSM Tree. Badger inherits the idea of iterator combination from leveldb, encapsulating the reading path of pendingWrites as an Iterator, and combining it with other Iterators such as MemTableIterator and TableIterator through MergeIterator to form the final Iterator:

// NewIterator returns a new iterator. Depending upon the options, either only keys, or both

// key-value pairs would be fetched. The keys are returned in lexicographically sorted order.

// Using prefetch is recommended if you're doing a long running iteration, for performance.

//

// Multiple Iterators:

// For a read-only txn, multiple iterators can be running simultaneously. However, for a read-write

// txn, iterators have the nuance of being a snapshot of the writes for the transaction at the time

// iterator was created. If writes are performed after an iterator is created, then that iterator

// will not be able to see those writes. Only writes performed before an iterator was created can be

// viewed.

func (txn *Txn) NewIterator(opt IteratorOptions) *Iterator {

if txn.discarded {

panic("Transaction has already been discarded")

}

if txn.db.IsClosed() {

panic(ErrDBClosed.Error())

}

// Keep track of the number of active iterators.

atomic.AddInt32(&txn.numIterators, 1)

// TODO: If Prefix is set, only pick those memtables which have keys with

// the prefix.

tables, decr := txn.db.getMemTables()

defer decr()

txn.db.vlog.incrIteratorCount()

var iters []y.Iterator

if itr := txn.newPendingWritesIterator(opt.Reverse); itr != nil {

iters = append(iters, itr)

}

for i := 0; i < len(tables); i++ {

iters = append(iters, tables[i].sl.NewUniIterator(opt.Reverse))

}

iters = append(iters, txn.db.lc.iterators(&opt)...) // This will increment references.

res := &Iterator{

txn: txn,

iitr: table.NewMergeIterator(iters, opt.Reverse),

opt: opt,

readTs: txn.readTs,

}

return res

}

Badger will store commitTs as a suffix of the key in the LSM Tree, and the Iterator will also be aware of the timestamp during iteration, iterating according to the snapshot data at the readTs moment.

This resembles with the concept of leveldb’s sequence number and Snapshot.

Transaction Commit

The entry point for transaction commit is in the Commit() function, which calls the commitAndSend() function as the main logic. The process roughly includes:

- Perform transaction conflict detection through

orc.newCommitTs(txn), if there’s no conflict, obtain thecommitTstimestamp - Loop through the Entries in pendingWrites and duplicateWrites to bind commitTs to their version, and bind

commitTsto the stored key - Call

txn.db.sendToWriteCh(entries)to make the write buffer enter disk writing - After waiting for the disk write to complete, notify

orc.doneCommit(commitTs), moving the position of txnMark

newCommitTs internally initiates conflict detection and expired transaction cleanup, and tracks the transaction to commitedTxns:

func (o *oracle) newCommitTs(txn *Txn) uint64 {

o.Lock()

defer o.Unlock()

if o.hasConflict(txn) {

return 0

}

var ts uint64

o.doneRead(txn)

o.cleanupCommittedTransactions()

// This is the general case, when user doesn't specify the read and commit ts.

ts = o.nextTxnTs

o.nextTxnTs++

o.txnMark.Begin(ts)

y.AssertTrue(ts >= o.lastCleanupTs)

if o.detectConflicts {

// We should ensure that txns are not added to o.committedTxns slice when

// conflict detection is disabled otherwise this slice would keep growing.

o.committedTxns = append(o.committedTxns, committedTxn{

ts: ts,

conflictKeys: txn.conflictKeys,

})

}

return ts

}

The conflict detection logic is simple, iterating through committedTxns, finding transactions committed after the current transaction started, and checking if the keys read by itself exist in the write list of other transactions:

// hasConflict must be called while having a lock.

func (o *oracle) hasConflict(txn *Txn) bool {

if len(txn.reads) == 0 {

return false

}

for _, committedTxn := range o.committedTxns {

// If the committedTxn.ts is less than txn.readTs that implies that the

// committedTxn finished before the current transaction started.

// We don't need to check for conflict in that case.

// This change assumes linearizability. Lack of linearizability could

// cause the read ts of a new txn to be lower than the commit ts of

// a txn before it (@mrjn).

if committedTxn.ts <= txn.readTs {

continue

}

for _, ro := range txn.reads {

if _, has := committedTxn.conflictKeys[ro]; has {

return true

}

}

}

return false

}

Transaction Cleanup

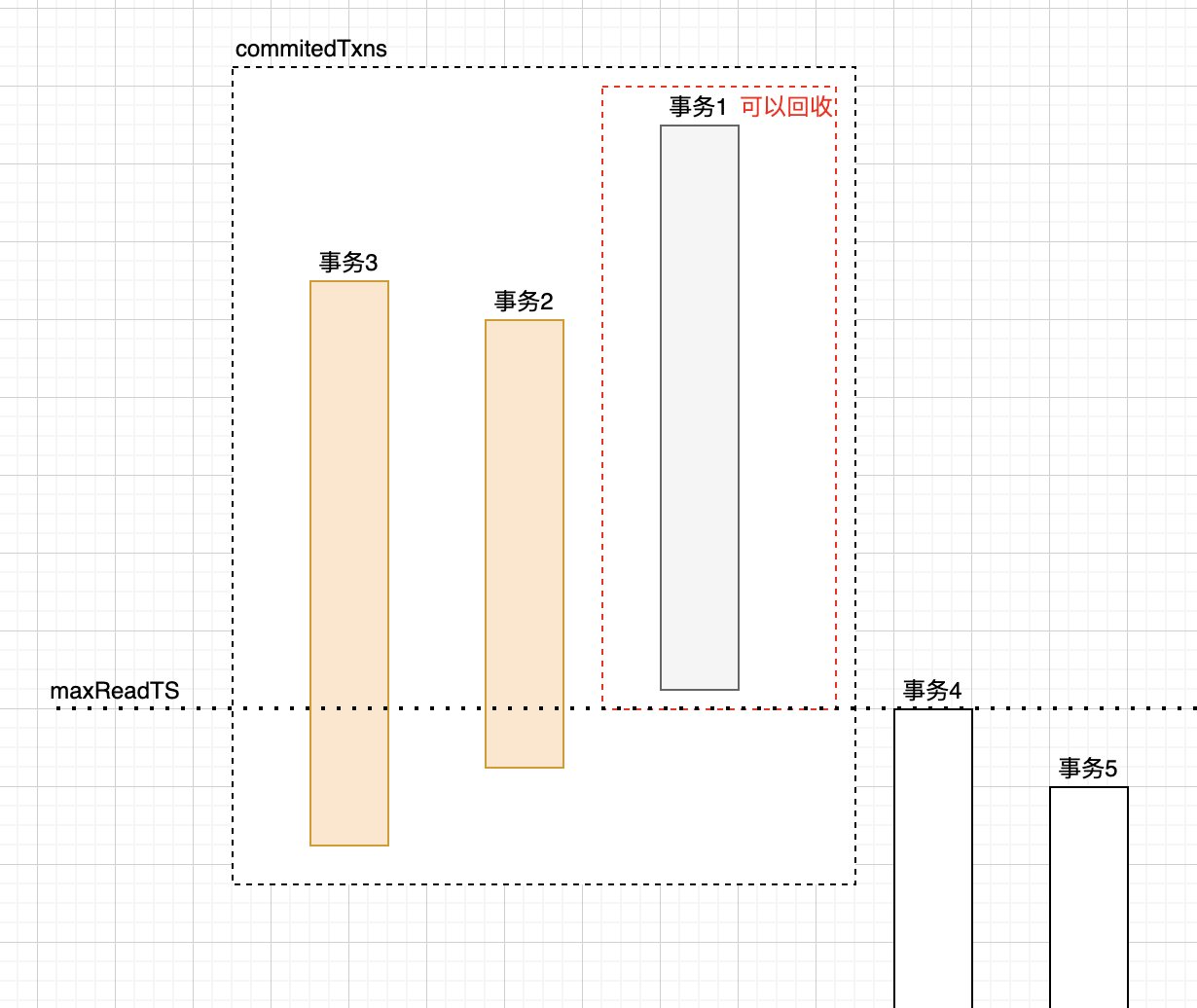

As mentioned earlier, transactions use the information in the committedTxns array for conflict detection during commit. The committedTxns array records information about recently committed transactions, and obviously cannot grow indefinitely.

So when can we clean up the committedTxns array? The key is the start timestamp of the earliest active transaction. If the commit timestamp of a historical transaction is earlier than the start timestamp of the currently active transaction, it doesn’t need to be considered during conflict checks, so it can be recycled in committedTxns.

func (o *oracle) cleanupCommittedTransactions() { // Must be called under o.Lock

if !o.detectConflicts {

// When detectConflicts is set to false, we do not store any

// committedTxns and so there's nothing to clean up.

return

}

// Same logic as discardAtOrBelow but unlocked

var maxReadTs uint64

if o.isManaged {

maxReadTs = o.discardTs

} else {

maxReadTs = o.readMark.DoneUntil() // Get the earliest readTs of currently active transactions in the readMark heap

}

y.AssertTrue(maxReadTs >= o.lastCleanupTs)

// do not run clean up if the maxReadTs (read timestamp of the

// oldest transaction that is still in flight) has not increased

if maxReadTs == o.lastCleanupTs {

return

}

o.lastCleanupTs = maxReadTs

tmp := o.committedTxns[:0]

for _, txn := range o.committedTxns {

if txn.ts <= maxReadTs {

continue

}

tmp = append(tmp, txn)

}

o.committedTxns = tmp

}

The oracle records lastCleanupTs to record the timestamp of the last cleanup, avoiding unnecessary cleanup operations.

Summary

- Transaction-related structs in badger include

Txnandoracle. The information insideTxnmainly includes start timestamp, commit timestamp, and list of read and written keys. On the other side,oracleacts as a transaction manager, maintaining a list of recently committed transactions, global timestamp, and the earliest timestamp of currently active transactions internally. - Transaction timestamps are logical timestamps, incrementing by 1 each time a transaction commits.

- The conflict detection logic in SSI transactions is to find the list of transactions that committed during the current transaction’s execution period, and check if there’s an overlap between the list of keys read by the current transaction and the list of keys written by these transactions.

- The

WaterMarkstruct internally is a heap, used to manage and find the segments of transaction start and end. ThetxnMarkeroforacleis mainly used to coordinate the time window between waiting for Commit timestamp assignment and disk writing, whilereadMarkermanages the earliest timestamp of currently active transactions, used for cleaning up expiredcommittedTxns.