ZGC is a new garbage collector introduced in jdk11, promising pause times of no more than 10ms, and these pauses are independent of heap size, supporting heaps up to terabytes.

As a fan of Go, you might think Go’s GC is already pretty good, right? It only has a little STW during Initial Mark, and regular GC pauses are usually under a millisecond? In reality, Go’s GC is still far from ZGC’s promises, especially when dealing with large heaps. It lacks compaction, and running compaction has many benefits:

- Prevents heap fragmentation, making memory allocation just a pointer jump away;

- After compaction, related objects are usually adjacent in memory, improving locality;

- Enables truly fast memory reclamation, with compaction time only related to active objects, not the total number of objects. The smaller the ratio of active objects to all objects, the higher the reclamation efficiency. In contrast, Go’s sweep overhead is directly related to the number of objects;

However, concurrent compaction is very challenging in engineering. Before ZGC, the only other option in the industry was Azul System’s Pauseless GC. Compaction means relocating object pointers. In CMS and G1GC, compaction and relocation are done during young generation STW.

This requires a mechanism to perform object relocation concurrently.

Load Barrier

In ZGC, this is the Load Barrier mechanism. It’s quite different from the Write Barrier in CMS/G1GC, including INC Barrier and SATB Barrier, which all activate when “modifying external references of an object.”

Load Barrier doesn’t directly oppose Write Barrier; it activates when “dereferencing a heap pointer”:

Object o = obj.FieldA

<Load barrier>

Object p = o // no barrier, it's not dereferencing any heap reference

It does more than Write Barrier and has different logic in different stages, not only tracking Mark but also initiating object movement (Relocate) and redirecting references (Remap), modifying pointers in place to point to new object addresses.

Two questions to consider:

- In tracking Mark, Write Barrier tracks every write operation, enqueuing marking operations. But in the Load Barrier scenario, enqueuing on every read operation would be a significant overhead, and these repeated enqueue operations are meaningless. A reference that has been accessed multiple times only needs to be enqueued once;

- How do you know if an object needs to be Relocated? Similarly, an object only needs to be Relocated once per GC cycle. Once relocated, it shouldn’t be attempted again;

Colored Pointer & Multi-Mapping

For these two types of metadata, ZGC uses a Colored Pointer technique, storing directly in the pointer:

- Marked pointers are tagged with a Marked flag, so next time you see this pointer, don’t repeat the Mark enqueue.

- Redirected pointers are tagged with a Remapped flag, indicating successful transfer, so don’t attempt Relocate on it again.

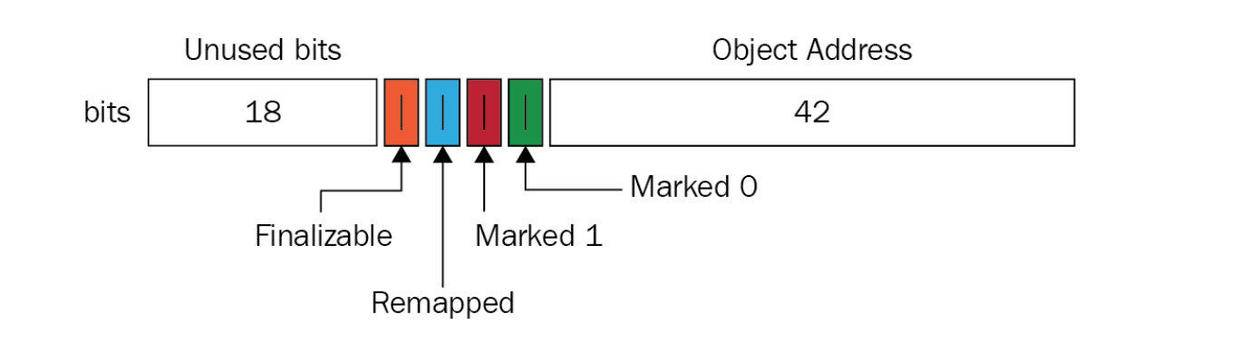

ZGC has a design limitation, supporting only 64-bit architectures. As we know, 64-bit architectures often only use 48 bits for addressing, leaving 16 bits unused, which can be used to store metadata.

Here are 4 bits of metadata:

- Finalizable: For destructor handling;

- Remapped: Indicates the reference has been redirected;

- Marked0 and Marked1: Indicate the pointer has been marked;

Ignore the Finalizable bit for now.

Among Remapped, Marked0, and Marked1, only one bit is 1 at a time, the others are 0.

Some architectures like ARM support Pointer Masking, telling the CPU a Pointer Mask, and the CPU will ignore the specified bits when dereferencing. Unfortunately, x86 doesn’t have this mechanism, so ZGC uses a Multi-Mapping mechanism:

+--------------------------------+ 0x0000140000000000 (20TB)

| Remapped View |

+--------------------------------+ 0x0000100000000000 (16TB)

| (Reserved, but unused) |

+--------------------------------+ 0x00000c0000000000 (12TB)

| Marked1 View |

+--------------------------------+ 0x0000080000000000 (8TB)

| Marked0 View |

+--------------------------------+ 0x0000040000000000 (4TB)

Mapping Remapped View, Marked1 View, and Marked0 View all to the same memory block! This achieves the same effect as Pointer Masking.

Mark and Relocate

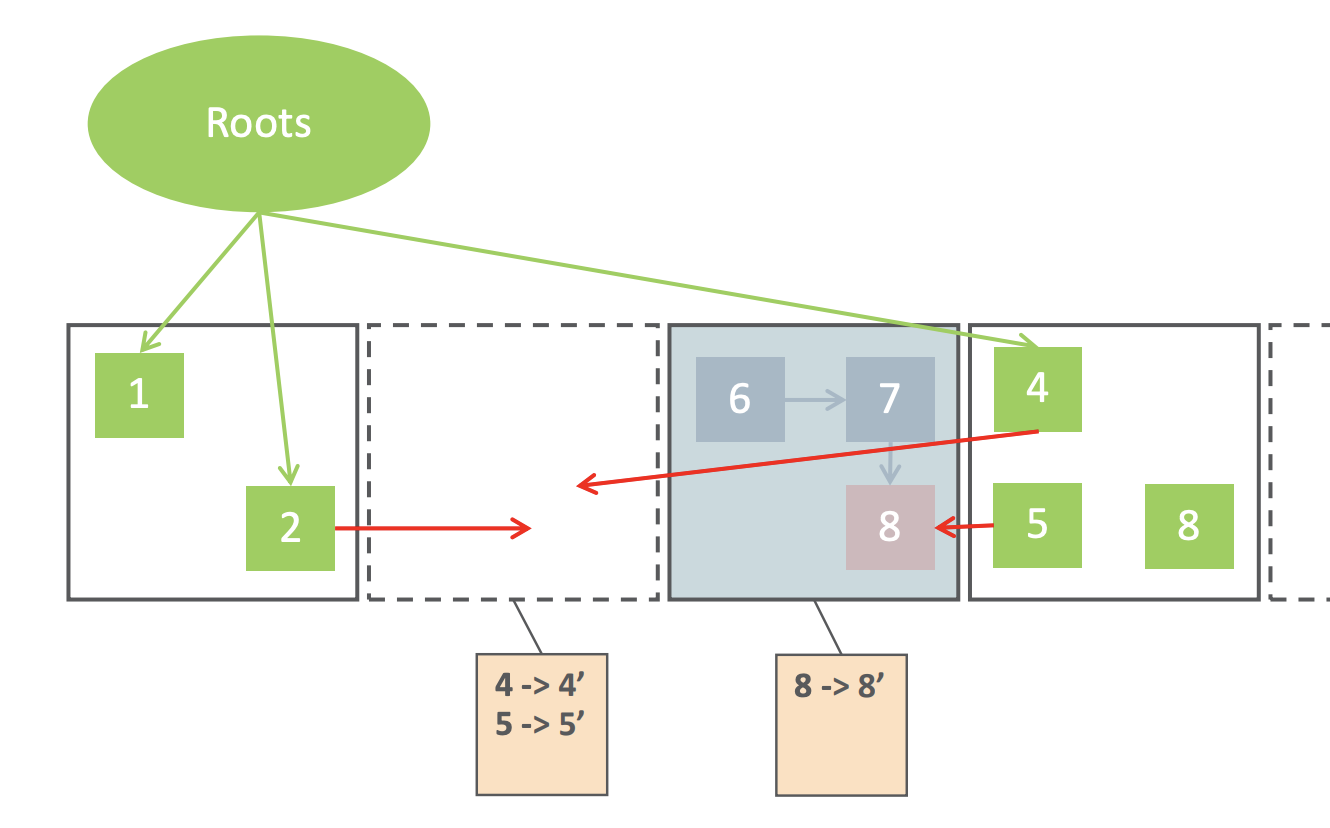

Load Barrier does different things at different stages. During the Mark phase, Load Barrier adds the accessed objects to the mark queue and then writes the mark information to the page’s Bitmap. As mentioned earlier, adding the same reference to the mark queue twice is unnecessary, so we add a Marked0 or Marked1 flag to the pointer. If the pointer with the Marked flag is accessed again, it won’t be added to the mark queue again.

After the Mark phase, the marked objects, which are considered live, can be moved. ZGC doesn’t move all objects at once but, like G1GC, selects a subset of pages called the Relocation Set. Each page in the Relocation Set has a Forwarding Table to store the object’s move status. The design of Relocation Set + Forwarding Table makes the execution time of the Relocation phase more controllable and saves memory overhead for pointer redirection information. In contrast, SGC 1.0 maintains a Forwarding Pointer in each object header, which is less efficient than ZGC’s Forwarding Table.

During the Relocate phase, GC threads traverse the objects in the Relocation Set to move them. When Load Barrier encounters a pointer in the Marked state, it checks if the reference exists in the Forwarding Table. If yes, it modifies the pointer to the new address and marks it as Remapped. If no, it initiates the move and updates the Forwarding Table. There’s a race condition here, as other threads and GC threads may concurrently perform Relocate, so a CAS arbitration is used.

The Relocate phase completes the move of objects in the Relocation Set, but the pointer redirection (Remap) is only initiated based on Load Barrier. A live object during the Relocate phase may not be truly accessed, so the reference remains in the Marked state and will still need to check the Forwarding Table on the next access.

Let’s revisit a question: Why are there two mark bits, Marked0 and Marked1?

ZGC will “coincidentally” remap all pointers in the Marked state from the previous round during the next Mark phase when traversing all objects and references. After completing the new Mark phase, all pointers in the previous Marked state will converge to the Remapped state, and all Forwarding Tables can be released. In short, the next Mark phase uses information from the previous Mark phase, so two mark bits are used for differentiation.

References

- https://www.zhihu.com/question/42353634

- ZGC 原理是什么,它为什么能做到低延时?

- http://paperhub.s3.amazonaws.com/d14661878f7811e5ee9c43de88414e86.pdf

- http://cr.openjdk.java.net/~pliden/slides/ZGC-Jfokus-2018.pdf

- https://dinfuehr.github.io/blog/a-first-look-into-zgc/

- https://blog.plan99.net/modern-garbage-collection-part-2-1c88847abcfd

- https://www.baeldung.com/jvm-zgc-garbage-collector