Kafka’s data reliability totally depends on replication instead of a single-machine fsync. To put it simply, Kafka Replication is designed like this:

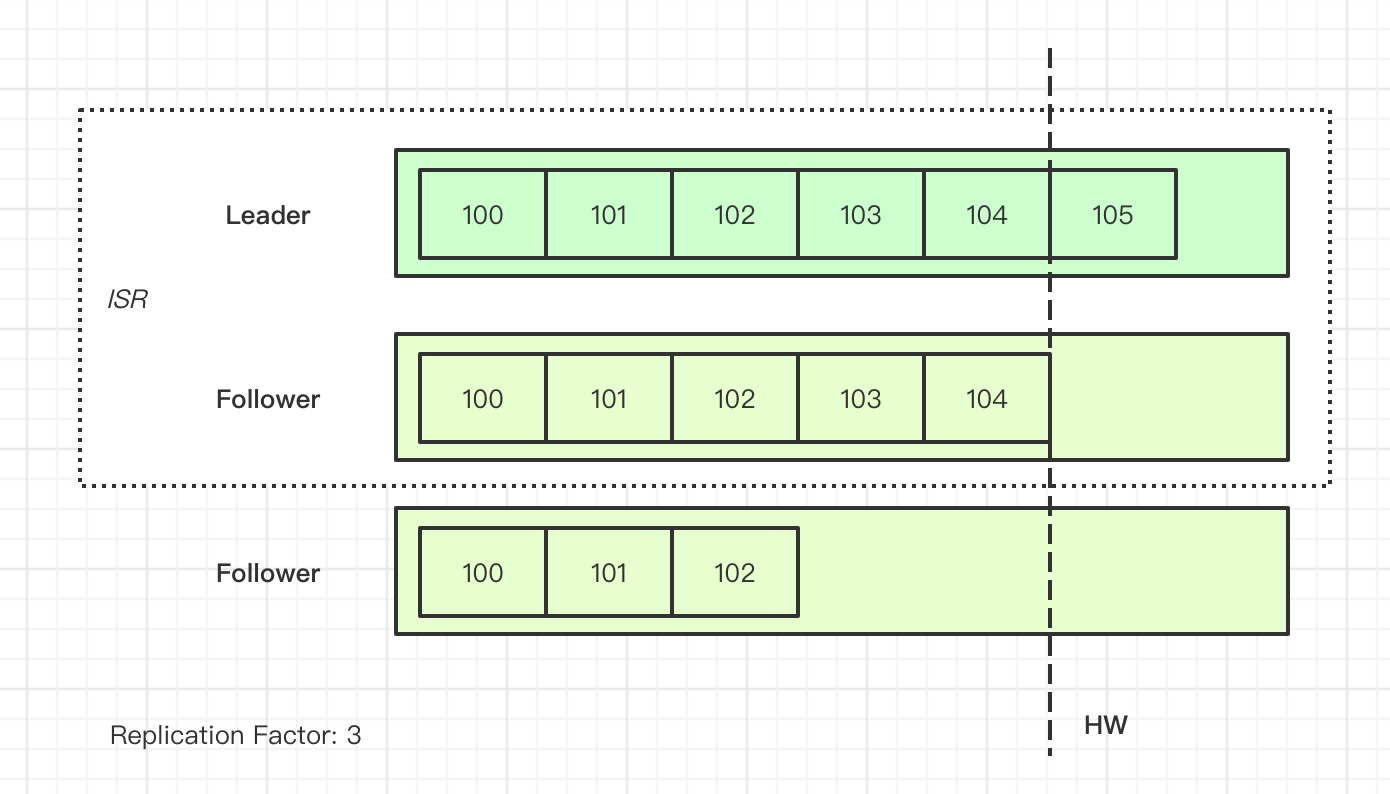

Partition is the basic unit of replication. Each Partition has multiple Replicas, one of which is the Leader. The Leader handles all read and write interactions with Consumers, while Followers pull data from the Leader via Fetch RPC. The default.replication.factor parameter determines how many Replicas a Partition in a Topic has.

The Leader maintains an ISR (In-Sync-Replica) list, which is the set of Followers considered to be in normal sync status. Kafka judges whether a Replica is still in ISR based on the replica.lag.time.max.ms parameter. If a Follower hasn’t synced with the Leader for a long time, the Leader will consider kicking this Follower out of ISR.

Unless unclean.leader.election.enable is set, the new Leader is always elected from ISR. min.insync.replicas determines the minimum number of ISRs each topic can accept. If the number of surviving ISRs is too small, the producer side will throw an exception.

The Producer can configure request.required.acks to decide the durability level of messages. 0 can be considered as Fire and Forget, 1 is receiving ack from the Leader, and all is receiving ack from all ISRs.

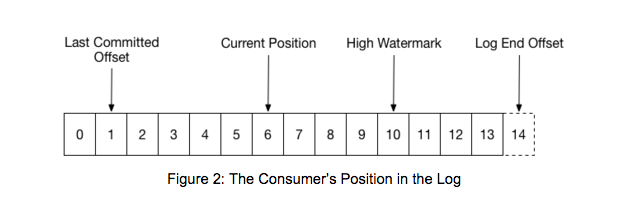

Once the Producer’s message is synced to all ISRs, the index of this message can be set as HW (High Watermark). Messages with an index less than HW are considered “Committed.” Consumers can only see messages greater than HW.

Here’s a simple diagram:

The design of ISR and HW is not found in asynchronous replication or semi-synchronous replication like MySQL. So, why do we need ISR and HW mechanisms?

HW

“High Watermark” is a common term in streaming processing systems, meaning existing data but invisible to readers. For Kafka Consumers, there are several offsets:

The data fetched by Consumers may reach LEO, but only data before HW will be returned to users. The significance of HW here is that it guarantees that the data read by users is persisted to all ISRs. Even if the Leader crashes and switches, it still guarantees that the same index message read by users will not change. For the message queue scenario, it’s better to lose messages than to have messages that have been consumed change when re-consumed. If the same index message changes when re-consumed, the monotonic order of messages is not valid for external systems, which means data corruption.

ISR

The design of ISR is probably largely for throughput performance considerations. Imagine, if acks = all means syncing messages to all Followers for full sync, then if a Follower restarts, it will block all writes, and the blocking time depends on the restart time. This host might never come back.

The ISR mechanism elegantly solves this problem: The Leader continuously checks the sync status of Followers. If a Follower cannot maintain sync status, it will be removed from ISR and will no longer block writes.

In the past, Kafka judged the sync status of ISR through the replica.lag.max.messages parameter, by determining the sync difference between Follower and Leader through the index carried by Follower’s Fetch request. However, as mentioned in the article “Hands-free Kafka Replication: A lesson in operational simplicity,” judging sync status by the difference in message count can easily lead to misjudgments: If the throughput of a topic suddenly increases, the increase in message difference is reasonable, but it doesn’t mean the Follower is out of sync. In subsequent versions, it was changed to uniformly judge sync status by the lag time specified by the replica.lag.time.max.ms parameter.

How to Ensure No Message Loss?

The definition of persistence in DBMS is to ensure that successfully written data is never lost, but errors during writing do not affect system persistence. This is different from message systems, where errors during writing also mean data loss when used as a data pipeline. So, how to ensure no message loss?

Kafka Producer stores messages in a buffer on the client side. If you can’t afford to lose data, it’s better to block and wait when the buffer is full instead of throwing an error. If you don’t want to lose any data, infinite retries make sense. But here’s a catch: if there are multiple concurrent requests from Producer to broker, retries can mess up the order of messages. So, if you care about the order, you should limit the number of concurrent requests to 1.

According to Kafka’s semantics, Consumer can achieve At Most Once with Auto Commit. If you want At Least Once, the Consumer should manually commit the offset after confirming the business processing is done. If you don’t want to lose any data, you should manually commit to ensure At Least Once semantics.

Here’s a summary of configurations related to “not losing messages”:

# producer

acks = all

block.on.buffer.full = true

retries = MAX_INT

max.inflight.requests.per.connection = 1

# consumer

auto.offset.commit = false

# broker

replication.factor >= 3

min.insync.replicas = 2

unclean.leader.election = false

To “not lose messages,” it’s better to choose blocking behavior over Fail Fast. This is perfect for scenarios like canal, which acts as a data pipeline. However, the same configuration can be risky in online business systems. Blocking behavior might freeze the business process, so you need to make some trade-offs. At the very least, pay attention to whether max.block.ms is still the default 60s. In engineering, some use a local persistent KV Store to temporarily store data, avoiding blocking on the Producer side. This is a gamble that two different components won’t crash at the same time.

References

- https://www.cnblogs.com/huxi2b/p/7453543.html

- Kafka Reliability - When it absolutely, positively has to be there

- Hands-free Kafka Replication: A lesson in operational simplicity - Confluent

- https://docs.confluent.io/current/installation/configuration/producer-configs.html

- https://www.cloudkarafka.com/blog/2019-09-28-what-does-in-sync-in-apache-kafka-really-mean.html